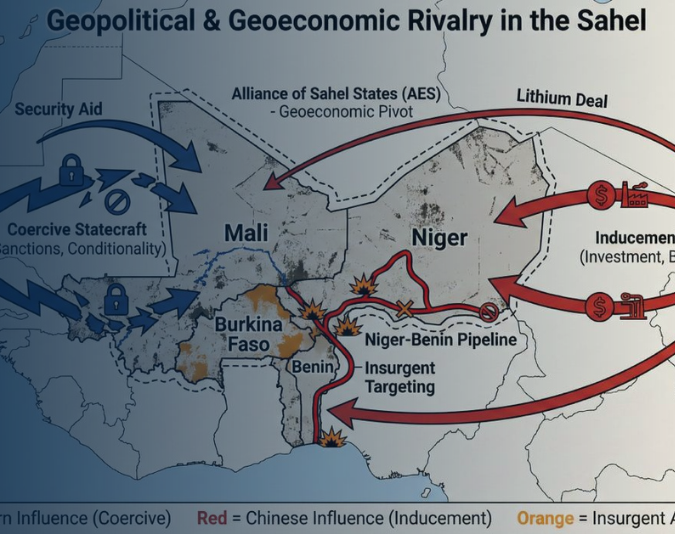

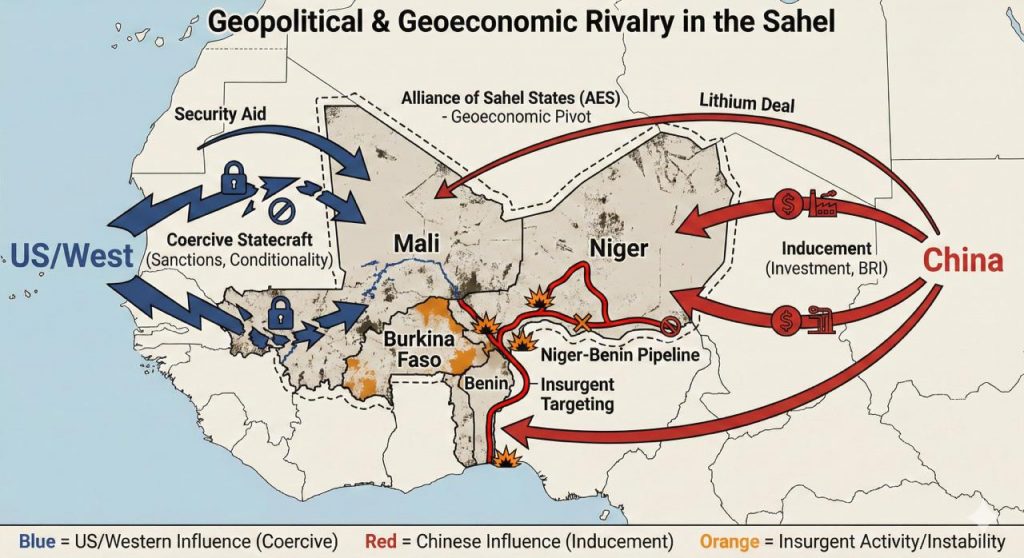

American coercive statecraft vs Chinese inducement

Africa, a region that continues to struggle to consolidate sovereignty and self-reliance, is increasingly shaped by a global shift from traditional geopolitics toward a more explicitly geoeconomic order. The economic competition between major powers such as the United States and China now conditions the national security environment of states caught between them, as economic instruments are increasingly deployed as tools of strategic influence. This dynamic is particularly evident in the central Sahel, where the conflict has evolved from a counter-terrorism fight into a theater of economic strangulation. Western geoeconomic coercion has backfired, triggering a strategic realignment toward China and enabling insurgent groups to exploit this resulting fragility through economic means, reaffirming the idea that geopolitical conflicts are indeed influenced by geoeconomics.

The U.S. (or Western) approach relies heavily on coercive statecraft, particularly through sanctions, discriminatory trade policies, and energy governance. Western foreign assistance is often explicitly geoeconomic, as it is characterized by conditionalities tied to geopolitical interests such as governance or transparency requirements. The USAID Resilience in the Sahel Enhanced initiative, launched in 2014 and temporarily frozen in early 2025, illustrates how deeply Sahelian states depend on major powers’ willingness to provide assistance. The effectiveness of coercive tools has become increasingly uncertain, geoeconomic power is now more diffused and multipolar, making it easier for targeted states to substitute partnerships rather than comply with external pressure.

On the other hand, the Chinese model emphasizes inducement. China’s “no-strings-attached” foreign investment in infrastructure, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, is leveraged to encourage shifts in diplomatic alignment. Resentment toward Western policies has contributed to alliance shifts in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, including their withdrawal from ECOWAS and the G5 Sahel, creating space for alternative external actors. This dynamic is best understood as geoeconomic fragmentation, defined by the IMF as a policy-driven reversal of integration guided by strategic considerations, which forces a reconfiguration of partnerships in the region and shapes how both states and non-state actors pursue power.

Source: own elaboration.

Geopolitics and geoeconomics in the Sahel

The Sahel has become a terrain where numerous actors intervene, both non-state and international powers, especially in the central region of Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. The decision by these states to withdraw from ECOWAS following sanctions for unconstitutional regime changes, and their subsequent creation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), proves that Western tools of control are no longer as effective as they once were.

This failure comes from the Western assumption that they held a monopoly on leverage. The withdrawal of security aid and trade privileges, such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act, was meant to force democratic reform, but in a context of a fragmented landscape as it is, it has created a geoeconomic vacuum rather than compliance. Because aid is fungible, the juntas viewed Western conditionalities as threats to their sovereignty and simply looked elsewhere. As they moved further away in their quest of decolonizing from the West, these three countries tilted towards the eastern bloc of allies, mostly Russia and China. And these new alliances fulfill a double function. First, they enhance security against the terrorist threat stalking the region, which was designated the “global epicenter of violent extremism” by the Global Terrorism Index of 2023. Second, they secure financing from China, which is meant to substitute previous dependencies on the West.

Crucially, this multipolar presence has far-reaching implications for the geoeconomic dynamics of the region. For instance, in 2019 China launched a project to construct the longest pipeline on the African continent, connecting Niger and Benin, providing a financial lifeline that bypasses Western aid. Similarly, Mali signed a strategic agreement with China for exploiting lithium, trading long-term mineral rights for immediate liquidity. It is clear that politics and economics are linked; in this specific case, the region’s stability depends on economic projects that are ultimately controlled by foreign powers’ stakes, revealing the paradox that in seeking to decolonize from the West, these states have merely swapped dependencies, trading defense reliance on the West for economic dependence on the East.

To understand the dynamics of the Sahel conflict, it is of utmost importance to consider how these “non-interference” policies are implemented on the ground. While Beijing prioritizes mutual benefit and political neutrality, engaging with regimes that lack the rule of law has inevitably exposed its economic projects to the region’s instability.

The most important finding is that the geoeconomic pivot to the East has made the region’s infrastructure a direct target. The aforementioned instability has intensified recently, given the type of terrorist attacks that have been perpetuated in Niger and in Mali. The Patriotic Liberation Front has explicitly targeted the China National Petroleum Corporation in the Agadem basin, sabotaging the Niger-Benin pipeline to cut off the junta’s income, while at the same time insurgents are using blockades as a weapon of economic pressure. ACLED data confirms that JNIM has imposed sweeping fuel and transport embargoes on key cities like Kayes and Nioro du Sahel in Mali, choking the trade routes that link the capital to the coast.

Consequently, while China historically has distinguished itself from Western interventionism by prioritizing commerce over ideology, its “non-interference” doctrine has blurred into a strategic paradox. By providing military aid to protect its assets, Beijing has trapped itself in a cycle of “transactional diplomacy” that has failed to buy loyalty. This support for unpopular regimes has led militants to increasingly view Chinese presence as illegitimate. Moreover, as violence spreads South toward the coast, Beijing is reportedly considering new naval logistics bases in Equatorial Guinea or Gabon to secure its shipping routes. This raises critical questions: Is China following the same militarized strategy with which the West once failed? And is it doomed to repeat the same errors? Ultimately, how can it maintain stable commercial activities if the region itself is geopolitically fundamentally unstable?

In conclusion, the US-China geoeconomic rivalry has transformed the conflict from merely geopolitics and political violence, into a resource and economic war. The failure of American coercion fueled a strategic pivot to China, yet this merely swapped dependencies without securing sovereignty. This shift has empowered insurgents to weaponize commerce, targeting critical infrastructure like the Niger-Benin pipeline to strangle the state. Ultimately, the region is trapped, as China’s slide into militarized protection proves that transactional diplomacy fails without security. Future analysis should specifically monitor whether the AES states can translate their mineral wealth into actual military capacity, or if the militarization of Chinese interests will simply provoke a new wave of anti-foreign insurgency. As global powers maneuver on this Sahelian chessboard, the question remains: will the region ever be more than a pawn in someone else’s game?