The Horn of Africa, situated between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, occupies a critical position in global geopolitics, as it lies along one of the world’s key maritime chokepoints connecting the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. Its location makes it a strategic crossroads between Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, but this potential is constrained by persistent political instability and economic fragmentation.

This region encompasses Ethiopia, Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea, while a broader definition of the Greater Horn includes Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and Sudan. This complex mosaic of states is characterized by weak governance structures that produce enduring insecurity, turning the Horn into a geopolitical vacuum and leaving room for external actors to intervene.

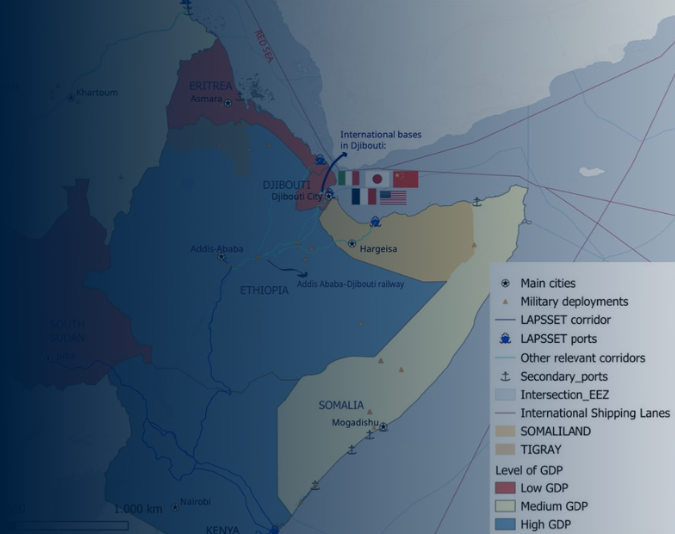

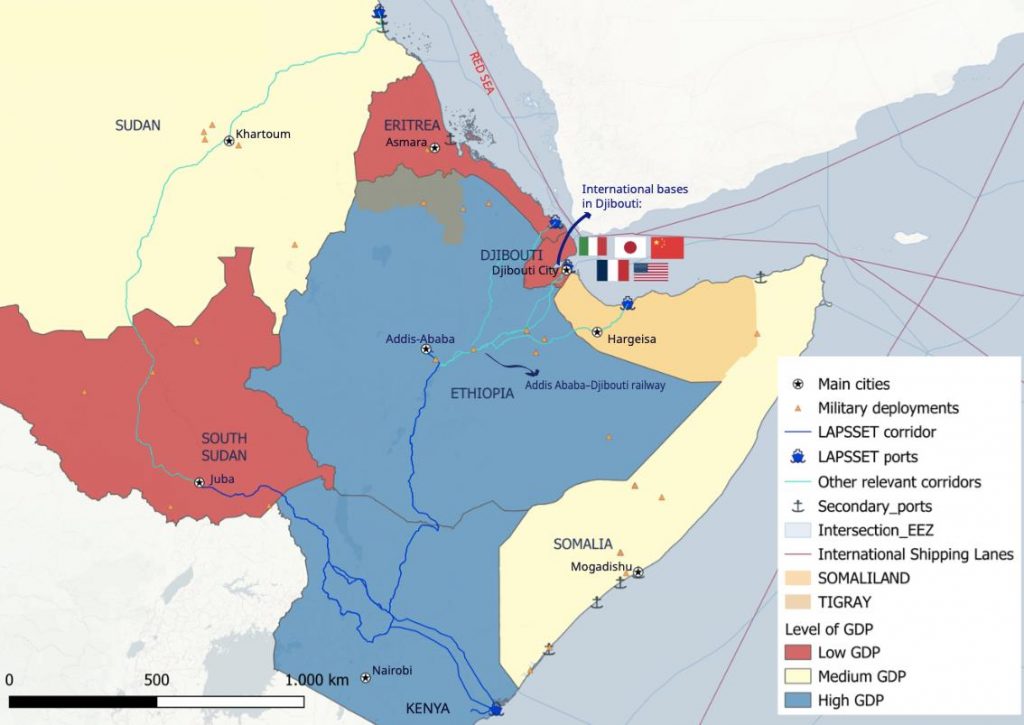

The economic dimension is equally significant. Ethiopia’s landlocked condition since Eritrea’s independence in 1993 has made it heavily dependent on Djibouti, which handles over 90% of Ethiopia’s trade. As noted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS, 2023), this dependency has both economic and strategic implications, influencing regional alignments and heightening competition over infrastructure such as the Addis Ababa–Djibouti railway and the Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor. In this sense, control over maritime space is a defining factor in the Horn’s geopolitics. The Red Sea and the western Indian Ocean have become zones of intensified strategic competition where global and regional powers’ interests intersect. Djibouti hosts military bases from the United States, China, France, and Japan, making it one of the most militarized territories per square kilometer in the world. Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have also projected influence by investing in port infrastructure and securing access to Eritrea’s and Somaliland’s coasts (Ministerio de Defensa, 2024).

Regional competition for access to the sea is intensified by ongoing territorial disputes. The main actor in this dynamic is Ethiopia, the world’s most populous landlocked country after Eritrea’s independence in 1993. Although a tripartite peace agreement was signed in 2018 between Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia to foster regional stability, these efforts have been undermined by renewed tensions among the three states (Bereketeab, 2024).

After Abiy Ahmed became Prime Minister of Ethiopia, the war against the TPLF (Tigray People’s Liberation Front) from 2020 to 2022 erupted, generating massive insecurity and destabilizing the region. Although this conflict produced a temporary alignment between Ethiopia and Eritrea, their tensions did not cease, particularly due to Eritrea’s fear that Addis Ababa might attempt to seize the port of Assab.

In 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a Memorandum of Understanding in which Somaliland agreed to grant Ethiopia access to 20 km of coastal territory in exchange for recognition of its sovereignty. This sparked immediate controversy, particularly among Somali politicians and the Islamist group al-Shabaab, which openly rejected the deal and called for international assistance. The agreement ultimately failed, as the international community reaffirmed Somalia’s territorial integrity and continued nonrecognition of Somaliland (ISPI, 2024).

In this context, the development of the LAPSSET corridor appears to offer some relief, connecting the Lamu Port on Kenya’s coast to South Sudan and Ethiopia, with links to other African regions. LAPSSET provides a direct alternative to the port of Djibouti, which currently dominates these nations’ sea access. Nonetheless, this small region remains a playground for major powers that profit from its geographic and strategic position, particularly by safeguarding vital sea routes such as the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait.

Ultimately, who will shape the future of the Horn of Africa: the states within it, or the powers surrounding it?